We met only briefly, 55-plus years ago. It was in Grand Rapids, a city on the western shore of Michigan, directly across the lake from Milwaukee. It was a Saturday; 9:04 a.m. to be exact. She named me Patrick.

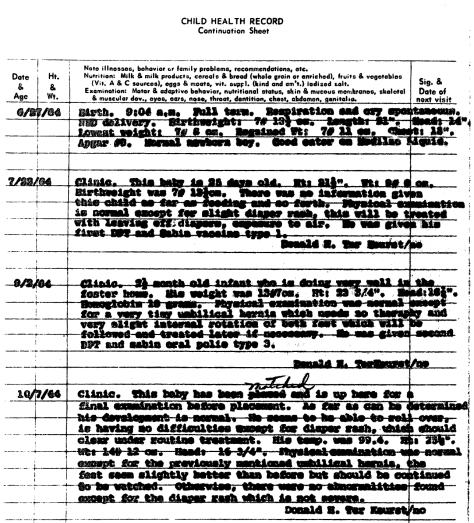

I won’t know on this side of eternity whether she had a chance to hold me or say goodbye before the nurses whisked me away to my new life. After spontaneous labor of 2 hours 14 minutes, there I was, all of 7 pounds 11 ounces, a “normal newborn boy,” according to the obstetrician’s notes.

Just like that, I was gone. So was she, the woman who gave birth to me in June 1964.

I thought of her often while growing up, and especially when I married and had my own children. After on-and-off searching for decades, I finally learned her identity in 2018. I so hoped to have a chance to meet her face to face, or at least to speak via telephone. I sent her letters and photographs of my children. It was not to be.

In August 2020, a Google search brought a real shock: she died in late March at age 78. I sat and stared at her photo in the the online obituary. I felt stunned, like being punched in the solar plexus. This can’t be. A few days earlier, I had decided I would make a cold call to her house and determine once and for all if she would speak with me. Now I can’t.

She was there, and then she was gone.

***

Hello, I must be going. That phrase is the title of a 1930 Marx Brothers song, the 1978 biography of comedian Groucho Marx and the second studio album of British pop icon and singer Phil Collins. The words came into my head and stuck there after I discovered that my birth mother had died.

I would never get a chance to meet her in this life.

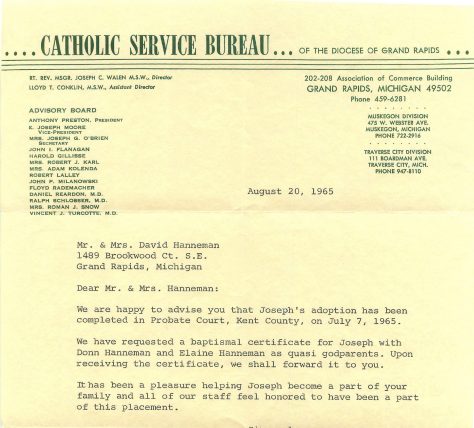

My adoption story began in September 1963, when a 21-year-old Michigan State University student unexpectedly became pregnant. After a few months, she moved from her home in East Lansing, Mich., to the Salvation Army Evangeline Home and Hospital in Grand Rapids. It was there she gave birth to me on June 27, 1964. I was turned over to the Catholic Service Bureau of the Diocese of Grand Rapids for adoption.

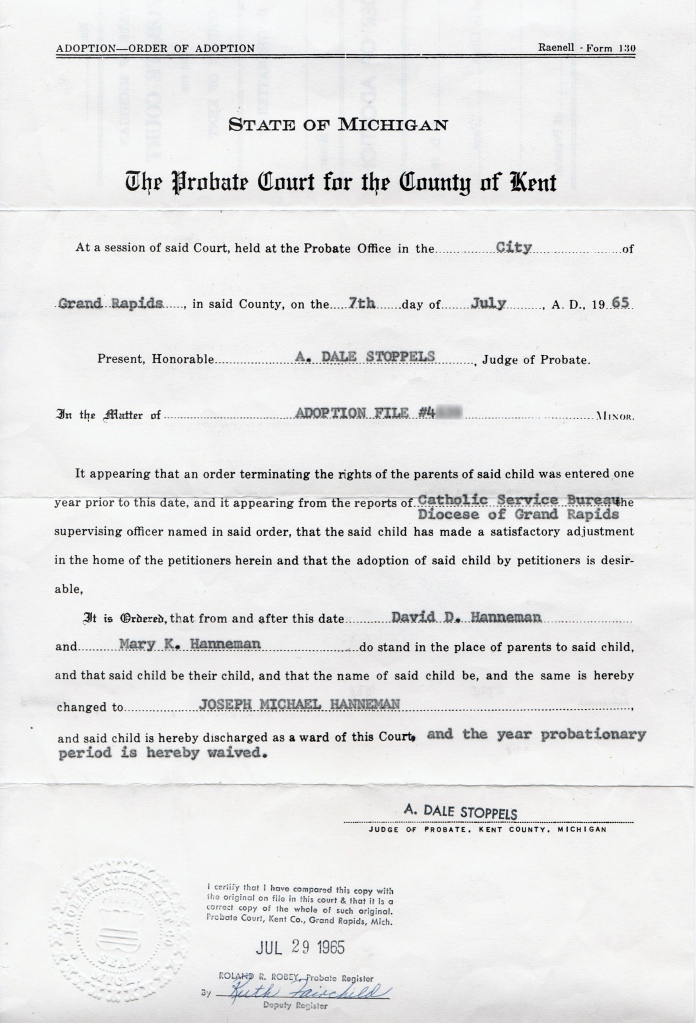

After three months in foster care, I was placed with a couple from suburban Milwaukee who had recently moved to the Kentwood section of Grand Rapids. Thus I began my life as Joseph Michael Hanneman, the son of David D. Hanneman of Mauston and the former Mary Katherine Mulqueen of Cudahy. My adoption was finalized on July 7, 1965, just in time for our family to move to Sun Prairie, Wis.

I had a very good upbringing by two faithful Catholic parents, but I was always curious about my birth parents. Who were they? How did I end up in the adoption system? Mom and Dad shared what they knew: my heritage was Irish, Polish and Swedish. One of my biological grandfathers was very tall, maybe even 6 foot 6 inches. That was about it. Not much to go on.

In 1986, after graduating from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I moved back home for a time while searching for a full-time job in newspaper journalism. I decided to put my reporting skills to work to learn more about my ancestry. Mom and Dad kept their important papers in a metal 4-gallon cherry can under the sink in the downstairs bathroom. Michigan cherries, of course. I found a packet of information there on my adoption. There was a finalized court order signed by Probate Judge A. Dale Stoppels of Kent County, Mich., and a letter from caseworker Schuyler B. Henehan at the Catholic Service Bureau of the Diocese of Grand Rapids. It wasn’t much, but it was a start.

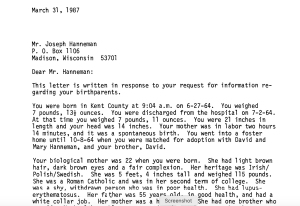

I wrote to the adoption agency and made a request for any and all information they had about my adoption. I also sent a letter to the Adoption Central Registry in Lansing to inquire if either of my biological parents had signed a waiver of privacy stating I could be told about their families. Not wanting my parents to feel hurt that I was doing this research, I rented Post Office Box 1106 at the U.S. Post Office in Downtown Madison. I received my first reply on March 31, 1987, from adoption search specialist Bonnie Kooistra at Catholic Social Services of Kent County. It didn’t provide any real clues to my birth mother or father’s identity, but did fill in some key details.

The letter said my birth mother was 22 at the time of my birth. She had light brown hair, dark brown eyes and a fair complexion. She stood 5 feet 4 inches tall. She was a Roman Catholic in her second term at Michigan State. The case workers at the time described her as “a shy, withdrawn person who was in poor health.” She had some serious medical issues. Her father was 55 and had a white-collar job, and her mother was a housewife, age 54.

My birth father was 25 when I was born, although there was no indication in the correspondence that he had any role in the adoption. That was typical in those days. I couldn’t even know if he was aware of my birth. He had red hair, green-gray eyes and freckles. Sounds familiar. He stood 5 feet 10 inches tall. He was a senior at Michigan State and adhered to no religion. “He was considered easygoing, kind, not temperamental,” the letter stated. His heritage was listed as Irish.

The letter further explained that I was not entitled to any identifying information under Michigan law. So they would not tell me the name of the hospital in which I was born. “I have never heard of a judge ordering a release of information,” Ms. Kooistra wrote. That made me frustrated and angry, but it appeared there was little I could do to obtain more information.

I didn’t make another attempt to learn more about my adoption until December 1994. I was now married with a nearly 3-year-old boy. I looked at his crop of red hair and started to wonder again about my ethnic heritage. I wrote to Catholic Social Services in Grand Rapids. This time, they were able to tell me more, due to changes in the law. The letter from adoption specialist Sandra Recker had a wealth of detail, including the county my birth parents came from (Ingham) and the name of the birth hospital (Salvation Army Evangeline Home and Hospital).

The letter said my birth mother was in her second term of college, and my birth father was a college senior who worked at the campus newspaper. She was in poor health with a chronic medical condition that could be life-threatening. Sandra included a photocopy of my medical record from my time at the hospital and in foster care. It contained four listings, including the day of my birth and three visits to the pediatric clinic. It was difficult to decipher, but eventually I determined the pediatrician was Dr. Donald H. Ter Keurst (1932-2004), a 1957 graduate of the University of Michigan Medical School.

I’d made good progress since my search began in the mid-1980s and, for now, this satisfied my curiosity about my personal history. But it continued to nag at me. I became very involved in genealogy research after the 2007 death of my Dad. I was able to trace his family history back to at least 1550 in the Baltic Duchy of Pomerania. But I could only guess at my own roots. That didn’t sit well with me.

During the 2014-2016 time frame, my two daughters began asking questions about their ethnic heritage and history. Now ages 15 and 18, they’d not expressed much interest before. So this gave some motivation for me to set out and hunt for clues to my origins. For the third time in 30 years, I wrote to Catholic Social Services in Grand Rapids, hoping to learn more than in the first two attempts. Based on that correspondence, it appeared my best bet to learn more would be to petition the court for a “confidential intermediary” who would locate the birth parents and see if they would be willing to establish contact.

At this time I was doing freelance writing for a European agency that develops articles and other content for web sites. (You can read their feature article on my search here.) One project was to analyze the variety of home DNA tests being marketed for genealogy. By the time this project was complete, I took a half-dozen DNA tests from vendors such as 23andMe, AncestryDNA, National Geographic, Family Tree DNA and MyHeritage. As it turned out, the writing project brought the breaks I needed to solve my history puzzle.

***

Nov. 27, 2016 was a monumental day. I received an email from 23andMe.com informing me that my DNA test results were available. I would finally get some estimate of my ethnic heritage. Was I really Irish, Polish and Swedish? As it turned out, that information was small potatoes. I clicked on the link for “DNA Relatives” and was confronted with a bunch of matches. Actually there were 1,500 matches, but the one atop the list stuck out: 26.22% DNA shared in 48 segments. Possible relationship: half-brother. What?

I stared at the results for a few minutes, still in shock. I didn’t expect to log in and find a brother atop my list of matches. The web site had a messaging feature. I quickly typed this note and sent it off to someone listed only by his initials:

Hello, my recently acquired DNA results indicate you might be my half brother, possibly on the maternal side. I was adopted in Michigan and have been seeking information on my birth parents.

23andMe Text Message

I logged onto the site every day, but didn’t see a reply until Dec. 5. Based on my new relative’s first note, I don’t think it sunk in that we were so closely related. “John, interesting results,” he wrote. John? A few minutes later, he came back and wrote, “Joe, I was adopted as well in Michigan, 1962. ….I would love to chat with you. It’s Monday Dec. 5, around 4 p.m. …hope to hear from you soon, Brother….!” We were able to talk via cell phone later that night. It was an incredible day. For Sean, I was his only known blood relative (aside from our birth mother and his own children).

It sure was nice to have someone with whom to confab about genealogy. We shared all of our research and looked for commonalities. Sean told me that he enlisted help from a Catholic social worker in 1993. She made contact with our birth mother. Our mother didn’t want to have contact with him at the time, but she filled out a long medical questionnaire. (Sadly, the social worker who spoke with our birth mother did not record her name or contact information, even in the confidential files.)

From that questionnaire I learned that my maternal grandfather was over 6 feet tall and 220 pounds; a “take-charge guy,” according to her notes. His wife was small and rather quiet, but very involved in their Catholic parish. She died tragically in 1965. Her father was a chemist. These clues would all come in handy before too long.

During the summer of 2018 we received two key clues from Sean’s relatives. One told us that our birth mother went by her middle name. Another weighed in with a huge clue: she thought our birth mother’s name was Pat Walsh. Whoa! With this bit of information and the other data points, I set off into my genealogy databases. It didn’t take long to find the likely candidate family. Her name was Mary Patricia Walsh, the only daughter of Howard C. Walsh and the former Mary Olive Switalski. She fit every data point from the questionnaire she sent Sean. We had solved the biggest mystery in either of our lives.

At about the same time, my DNA test results from AncestryDNA came in. I was an experienced Ancestry.com user and knew their database of users was huge compared to any other genealogy company. I got another shocker when viewing my DNA matches, another brother. This time, it turns out, it was from my birth father’s side. I sent a message to the account holder and waited.

In the mean time, I had several other matches who were likely second cousins, so I reached out to them while poking around their online family trees. Before the reply came from my new half-brother, I determined the identity of my birth father. Sadly, he died in December 2013 at age 74. Before I had the first phone conversation with my brother Dave, I obtained a letter from the adoption agency confirming my birth father’s identity. I will write more about Bill in a separate post. He was a good man, married for more than 50 years with two great children, Dave and Kelly.

***

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of learning the identity of my birth parents. While it did not lead to any in-person introductions, it opened up my entire genealogy. With hard work and research, I would soon be able to trace my maternal history to a village in County Kilkenny, Ireland; a rural area in Yorkshire, England; a city in Poland and somewhere in Sweden. Both maternal and paternal families had an emigration path that ran through Cincinnati and greater Ohio. Plenty of work to do.

My birth mother got married a little more than a year after my birth. She and her parents were communicants at St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church in East Lansing, Mich. A year after she married, her mother died very suddenly at age 55. My birth mother did go by her middle name: Tricia when she was younger, Pat in adulthood and later changed to Trish. She had one sibling, John Howard Walsh Sr., who died in 2015. Her three sons now live in the Carolinas, which is where she died on March 27 after battling cancer.

While my genealogy search did not lead to meeting either birth parent, I am much richer for the effort. I have six “new” half-siblings, three of whom I’ve gotten to know from a distance. I hope to visit Michigan next summer. The hospital where I was born is still there, although it’s no longer a health-care facility. There are many people to meet face to face.

We can start with “hello.” •

Epilogue: On Christmas Day 2020, I received an incredible gift: the remaining contents of my adoption case file. The nearly 20 pages of documents confirmed all I already knew. It added some wonderful detail, too. My full birth name was Patrick Kevin Walsh. It appears my birth mother did spend some time with me before I went into foster care in early July 1964. My foster care was either in a facility named McMillan or with a family with the McMillan surname. There are many other bits of information that are new to me. These documents scanned from microfilm turned out to be a wonderful Christmas present.

Howard C. Walsh ran for City Council in East Lansing.

Mary Patricia

Tricia exhibited a painting in 1954.

July 1965 wedding portrait from the Lansing State Journal.