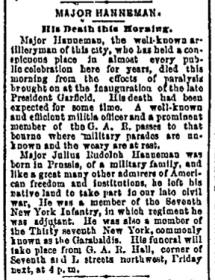

At some point in the long journey of family history research, it seems a given that you will likely never know what your earliest ancestors looked like. Through the donations of others, I’ve been blessed to discover photos of my Hanneman great-great grandparents. I never thought I’d see a photograph of Philipp Treutel, my great-great grandfather who died in 1891. Now, through the kindness of a stranger from Ohio, that has all changed.

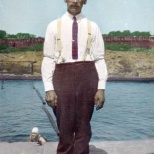

Through an incredible set of circumstances, earlier this week I received a 2.5-by-4-inch photo card labeled “Phillip Treutel.” In my research, I’ve never encountered another Philipp Treutel from the 1800s, so this very much got my attention. Philipp Treutel is my great-great grandfather, via my grandmother, Ruby V. (Treutel) Hanneman. As documented elsewhere on this site, Philipp came to America in 1854 from Königstädten, Germany, and settled in Waukesha County, Wisconsin. The photo image was almost ghosted it was so light. The pigments on the card stock had flaked away and faded, but the face was still visible.

There were two things I immediately wanted to do. One was to scan the image and see if I could darken the pigments and bring out more facial detail. The other was to investigate the photography studio, based on the photographer’s stamp on the back side. To accomplish the first goal, I ran the digital photo through several software programs and experimented with different tonal adjustments, filters and special effects. Many were useless or did little more than amplify the photo’s defects. But a few did improve the image, bringing out just enough detail to see his face better.

I then turned to the photographer, listed on the back as Bankes Gallery of Photographic Art in Little Rock, Arkansas. The photo was printed on what was called a carte de visite, or visiting card. These affordable, pocket-size calling cards were popular in the Civil War era. Thomas W. Bankes, owner of the photo studio, was a Civil War photographer who initially was based in Helena, Arkansas, documenting many of the gunboats along the Mississippi River. He photographed the overloaded steamboat SS Sultana the day before it sank, killing as many as 1,800 people, including Union soldiers returning home from the war.

In late 1863, Bankes moved his studio to Little Rock. He continued to photograph many Union soldiers during the federal occupation of the city in the latter part of the Civil War. This begged the question: what was Philipp Treutel doing in Little Rock? Was it during the Civil War or years after? Bankes operated a studio in the city well into the 1880s. Based on the carte de visite style of photo, it is a reasonable bet that Philipp’s photo was taken between 1864 and the late 1870s.

There are a couple possible explanations for Philipp being in Arkansas. Perhaps he was there to meet up with his younger brother, Sebastian Treutel, a Union soldier from Wisconsin who was discharged from the war with a disability in August 1863. We don’t know if Sebastian was ever sent to Little Rock, or when he returned to Wisconsin after his discharge. We don’t believe Philipp Treutel served in the Civil War, since his name does not appear in any of the state or federal veterans databases. Two of his brothers, Sebastian and Henry, both served with the 26th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment. Sebastian served in Company A, the “Flying Rangers,” and Henry was a member of Company G, the “Washington County Rifles.”

Perhaps Philipp was visiting another brother, Peter Treutel, whom we believe settled in Louisiana or Alabama after the family arrived in America. We know almost nothing about Peter. He was born on May 14, 1837 and baptized on May 17 at the Lutheran church in Königstädten, a village south of Russelsheim, Germany. A scrapbook kept by Emma (Treutel) Carlin, Philipp’s granddaughter, says Peter Treutel settled “in the South.” So far we have no documentary evidence of this, although we have records of a man we believe to be his son living near Mobile, Alabama.

Civil War records list a Confederate soldier named Pierre Treutel, who served with the Sappers and Miners. It’s unclear if this could be our Peter. Pierre Treutel enlisted in 1861 in Louisiana. Sappers built tunnels and miners laid explosives. According to Confederate military records found at Fold3.com, Pierre Treutel was a sapper in Captain J.V. Gallimard’s company of sappers and miners. Even if Pierre is the same person as Peter, it seems unlikely that Philipp Treutel would visit his younger brother during this time. As a Confederate soldier, Peter would have been subject to capture by Union forces in Arkansas. If Peter was a Confederate soldier, it could explain why the Treutel family in Wisconsin did not stay in touch with the Treutels of the South.

What do we know about Philipp Treutel? He was born Johann Philipp Treutel on August 7, 1833 and baptized on August 9 in the Lutheran church at Königstädten, Germany. He had a twin born the same day, although the twin was baptized a day earlier than Philipp. This most likely means the twin died on August 8, 1833. Church records don’t list a first name for the twin, only “Treutel.” Their parents were Johann Adam Treutel and the former Elizabeth Katharina Geier. In July 1854, Adam and Katharina left Germany for America with at least several of their children. It appears that some of the Treutel boys left Germany for America between 1849 and 1852. Shortly after arriving in Wisconsin, Philipp settled in the village of Mukwonago, where he worked as a blacksmith. By 1860, he had married Henrietta Krosch and they had their first child, Adeline Barbara.

At some points during and just after the Civil War years, Philipp lived and worked as a blacksmith in downtown Milwaukee. The 1863 Milwaukee city directory shows Philipp living and working at the southwest corner of Fifth and Prairie in Milwaukee. The 1867 Milwaukee directory shows him working as a blacksmith and living at 517 Cherry, right next door to his brother Henry. It is possible the Treutel family stayed in Mukwonago and Philipp shuttled back and forth, working in blacksmith shops in Milwaukee and Mukwonago.

While we don’t know of any official evidence Philipp was a soldier during the Civil War, the July 22, 1863 issue of the Daily Milwaukee Sentinel lists Philipp as a Civil War enrollee in “Class One” from Milwaukee’s Second Ward. His name appears along with his brothers Sebastian and Henry. It’s unclear what the listing means, since Sebastian and Henry were already fighting in the South with the 26th Wisconsin. It might have merely been a draft listing. More research will be needed, since this provides at least a hint that Philipp might have been involved in the war.

Philipp and Henrietta Treutel raised seven children: Adeline (1859), Lisetta (1861), Henry (1864), Charles (1869), Oscar (1874), Emma (1877) and Walter (1879). The family lived in the village of Mukwonago, where Philipp plied his trade as a blacksmith. His shop is found on the 1873 map of Mukwonago, located along the north side of what is now called Plank Road, just east of Highway 83. The family at some point moved from Mukwonago to the town of Genesee, near the hamlet of North Prairie in Waukesha County.

We have little documentary evidence of their time in Genesee. The 1890-91 Waukesha city directory lists him as “P.O. North Prairie.” Philipp died there on June 15, 1891 from “la grippe,” which is what they often called influenza at that time. His brief death notice in the June 25, 1891 issue of the Waukesha Freeman was listed under Genesee Depot, which is northeast of North Prairie. The newspaper misspelled his name as “Mr. Tradel,” while a nearby condolence notice under the town of Genesee said, “In the death of Trendall we have lost a good neighbor.” Is it too late to request a correction?

Philipp’s youngest child, Walter (1879-1948), is the father of our own Ruby Viola (Treutel) Hanneman. I placed the enhanced photo of Philipp Treutel next to one of Walter and noticed a strong resemblance.

Discovery of Philipp’s photo is a big development for Treutel family history. Our source for the photograph said she purchased the photo card at an estate sale in Minnesota or Wisconsin. Right now we’re examining other photos in her collection to determine if any show the Treutels or their relatives from Waukesha County. Stay tuned.

©2017 The Hanneman Archive