SHAWNEETOWN, Illinois — Children skipped happily along the streets of this southern Illinois town on the afternoon of Sunday, April 3, 1898. Sunday school had let out and the rest of the sunny day was theirs to claim. A large crowd of adults ambled along the walk, crossing Market Street and continuing on their way home. At the north end of Market Street, the levee that protects the town from the Ohio River was badly strained by rising water. But if the townsfolk were worried, it did not show on this spring day.

About 4:45 p.m., a 10-foot section of the levee collapsed and river water began pouring through the breach onto Market Street. The hole in the levee quickly grew to a half-mile wide, exploding into a wall of onrushing flood water that raced into the center of town. The flood rush hit the town like a blast from a double-barrel shotgun. Dozens of homes in the immediate path, many nothing more than shanties, were suddenly swept away. The small buildings were thrust along, some of them smashing against sturdier structures like the courthouse. Within mere moments, a quarter of Shawneetown’s homes were gone, the remains of which tumbled along in the rolling boils of a massive flood.

The people of Shawneetown were no strangers to floods. They had waged war with the Ohio River for generations. The Ohio always won the battle, but the people rebuilt time and again. As heavy spring rains swelled the Ohio again in March 1898, the older folks in town knew it could mean big trouble. But the relatively new levees were supposed to prevent it. Levees were built in 1884 after back-to-back years of devastating floods that twice wiped out much of the town. Today, the Ohio River again claimed its superiority with the ferocity of a jungle cat.

“About 50 small frame houses along the line of the levee to the south were crushed like toys,” witness T.J. Hogan of Omaha, Illinois said. Stunned residents scrambled for higher ground. Women on the streets struggled through the muddy waters, holding their babies aloft as the flood waters reached neck level. “The strongest houses, built especially to resist floods, went down like corn stalks,” wrote photographer Benneville L. Singley. “There was a wild rush for the hills. None had time to secure either treasure or clothing.”

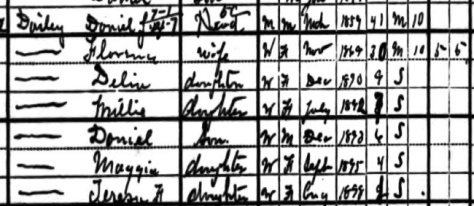

A few miles northwest of Shawneetown, the Daniel J. Dailey Jr. family was preparing for Sunday supper on their farm in North Fork Township. Florence (White) Dailey, 30, prepared the meal while the children helped ready the table. The Dailey home was a busy place, with Delia, Millie, Daniel and Maggie scuttling about. Maggie, just 2 ½, grew up to become our own Margaret Madonna (Dailey) Mulqueen of Cudahy, Wisconsin.

The Dailey and White families had farmed this area of Gallatin County since the early 1860s. Daniel J. Dailey Sr. brought his young family from Ohio about 1860. The 1860 U.S. Census shows the Dailey family consisted of Daniel, 30, Hannah, 26, Mary, 4, and Daniel J., 2. The White family, from which Florence (White) Dailey came, settled in Gallatin County nearly a decade before her birth. The 1860 census showed the White family included father Don, 24, mother Sarah, 24 and children Mary, 5, Wiley, 3, and James, 6 months. Florence was born in November 1869.

We don’t know how long it took word to reach North Fork about the massive breach in the levee. It was most likely the next morning. The news no doubt sent Daniel Dailey towards Shawneetown with other area farmers, while Florence (White) Dailey gathered supplies for what would soon become a massive relief effort. By nightfall on April 3, the river had flooded dozens of square miles in and around Shawneetown with water up to 15 feet deep.

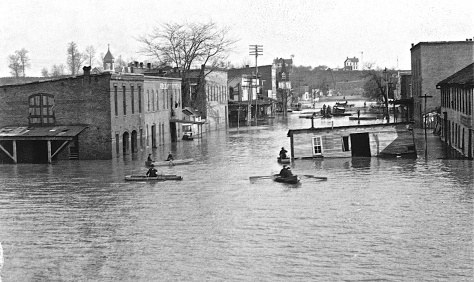

By morning, the town was devastated. Those who could scrambled to the roofs of their homes to escape the rising terror. Dozens raced into the Gallatin County Courthouse, the Riverside Hotel and the Ridgway Bank, seeking shelter on the upper floors of these sturdy structures. A few early rescue boats and canoes drifted into town and began rescuing the stranded. “Hundreds of those who escaped the rush of water were perched on roofs, trees and along the top of the levee,” a newspaper dispatch read. “They were taken from their dangerous positions as rapidly as possible.” Survivors were taken to nearby Junction City, where an emergency camp was established.

Upstream, carpenters, farmers and any able-bodied men began building flat boats that would be used to ferry supplies and people. When word reached dry land in nearby towns, frantic wires were sent to Springfield for help. The situation was pure panic. Newspapers across America carried dramatic headlines; FLOOD AT SHAWNEETOWN. Some predicted hundreds of deaths. One paper even pegged the toll at 1,000.

Meanwhile, rescuers shortly had weather to battle. The cold rains had started again, whipped by 30-mile-per-hour winds that made the sheets of rain cut like glass. Relief efforts were being coordinated at Ridgway, some 12 miles from Shawneetown. The governor sent more than 100 tents and rations for more than 1,000 people, but initially the displaced could rely only on the charity of neighbors and strangers. It would be weeks before the deep flood waters began to recede. Doctors hurried to the area to help prevent sanitary conditions from sickening the townsfolk.

On April 5, the Shawneetown relief committee released a statement and called for donations: “The whole town is submerged. One tract of twelve acres is about 15 feet under water; this was formerly covered with small dwellings and is now absolutely bare. On this tract the greatest loss of life occurred. It is evident that bodies cannot be recovered, nor any absolute knowledge of the number of deaths obtained until the waters abate.”

When the waters finally receded, the full toll of the disaster could be chronicled. There were 25 killed by drowning. Some 143 houses were demolished or rendered untenable. About half of those floated away on the rising river. The relief committee distributed more than $22,000 and helped rebuild many homes. Losses were estimated at in excess of $300,000.

Gallatin County Sheriff Charles R. Galloway suffered particularly stunning personal loss. After learning his daughters Dora, 19, and Mary, 12 were killed in the flood, he then learned of the drowning of his wife, Sylvester. Photographer Singley wrote that the sheriff’s hair “turned suddenly white from grief at the loss of his wife and two daughters.” In some cases, entire families were wiped out, such as Charles Clayton, his wife and their four children.

Until 1883, Shawneetown was completely at the mercy of the river. That year, after floods had again wiped out much of the village, construction was begun on a levee system. The levee was still incomplete in February 1884 when the river overpowered it, pouring floodwaters into the town. “Within 24 hours from that time, all the poorer people of Shawneetown were homeless, their houses drifting about and away in the turbulent flood,” read a report prepared for the Illinois legislature.

There was something in the community’s DNA that willed the folks to rebuild. This was a longstanding feature of life in Shawneetown. Morris Birbeck, writing his 1817 Notes on a Journey in America, remarked: “As the lava of Mount Etna can not dislodge this strange being from the cities which have been repeatedly ravished by its eruptions, the Ohio, with its annual overflowings, is unable to wash away the inhabitants of Shawneetown.”

As true as Birbeck’s observation was, the Ohio struck at Shawneetown with disastrous results again in 1913. That year, more than 1,000 people took up residence in tent cities built on the nearby hills. An emergency hospital was built to care for the injured and sick. In 1932, the levee was raised to 5 feet above the high-water mark from 1913. But nothing would hold back the flood waters in 1937, when what was called a 1,000-year flood swamped the town. After more than a century of floods and destruction, Shawneetown would not rebuild on the lowlands. The state and federal governments helped move the village onto hills 4 miles back from the river.

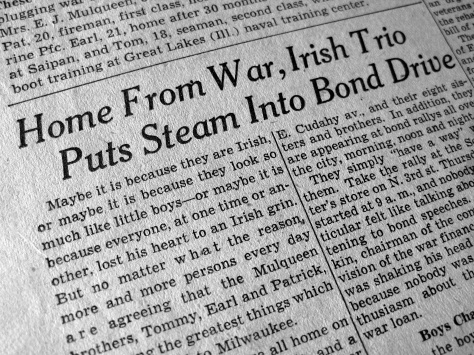

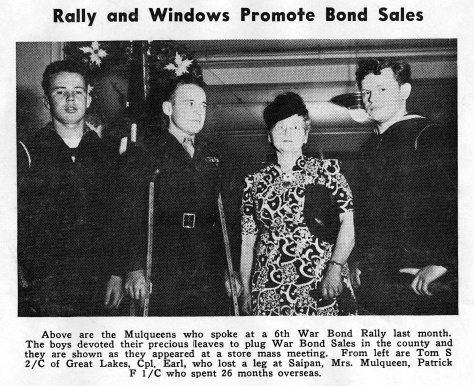

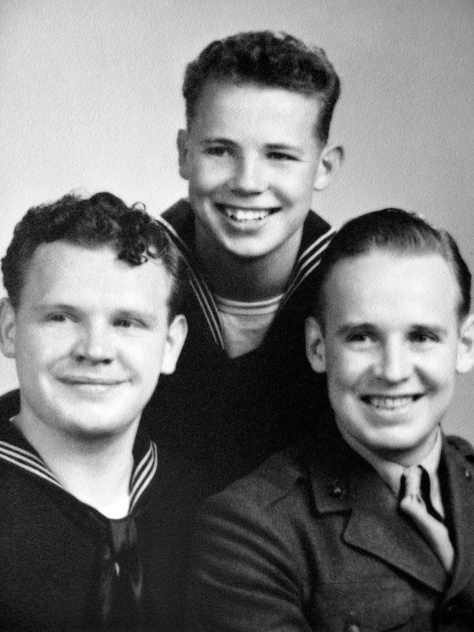

Margaret Dailey, who was referred to in Census documents as Maggie and Madge, moved away from North Fork and went to school at Northwestern University. She finished her studies in June 1920, and shortly after married a young man named Earl James Mulqueen in Racine, Wisconsin. The Mulqueen family home, which eventually relocated to Cudahy, welcomed 11 children between 1921 and 1944.

— This post has been updated with an additional photo of the flood, and a correction on the location of the first photo to Uniontown, Ky., rather than Shawneetown.

To see other photos of flood devastation at Shawneetown over the years, visit the Ghosts of Old Shawneetown.

©2015 The Hanneman Archive